DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMS THINKING: WHY ROBOTS MUST WORK ALONE TOGETHER

Key Insight: Robots work best when each part thinks independently and shares what it knows, not when everything asks permission from a central brain.

ROS2 FOUNDATIONSLEARNING JOURNEY

VED

1/8/202612 min read

A0 prerequisite

Purpose: Establish the foundational mental model—robots are inherently distributed agents. Teach decentralized thinking using real-world analogies before any ROS2-specific concepts.

This Article Answers

What makes a system "distributed"?

Why do robots need decentralized architecture instead of central control?

What breaks when you try to centralize everything?

How do independent agents coordinate without a boss?

Why is this thinking pattern necessary before learning ROS2?

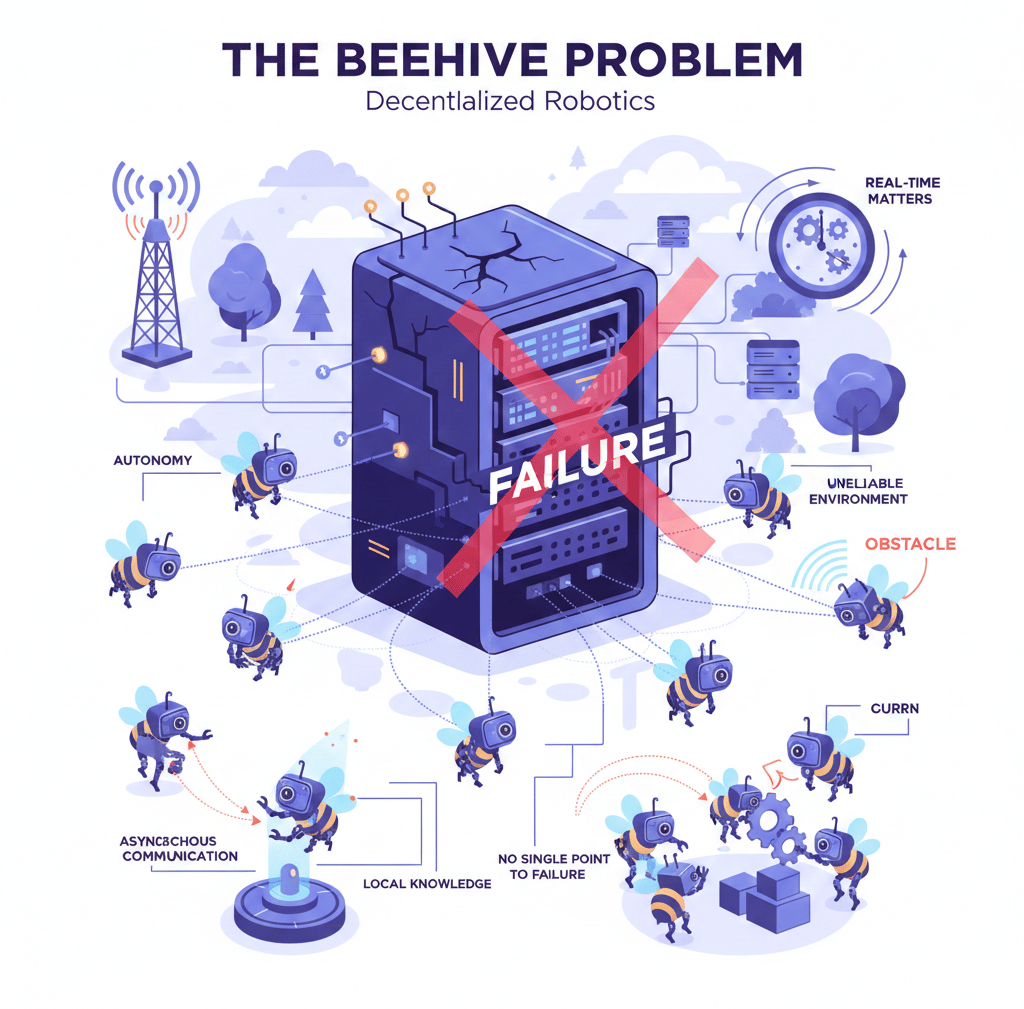

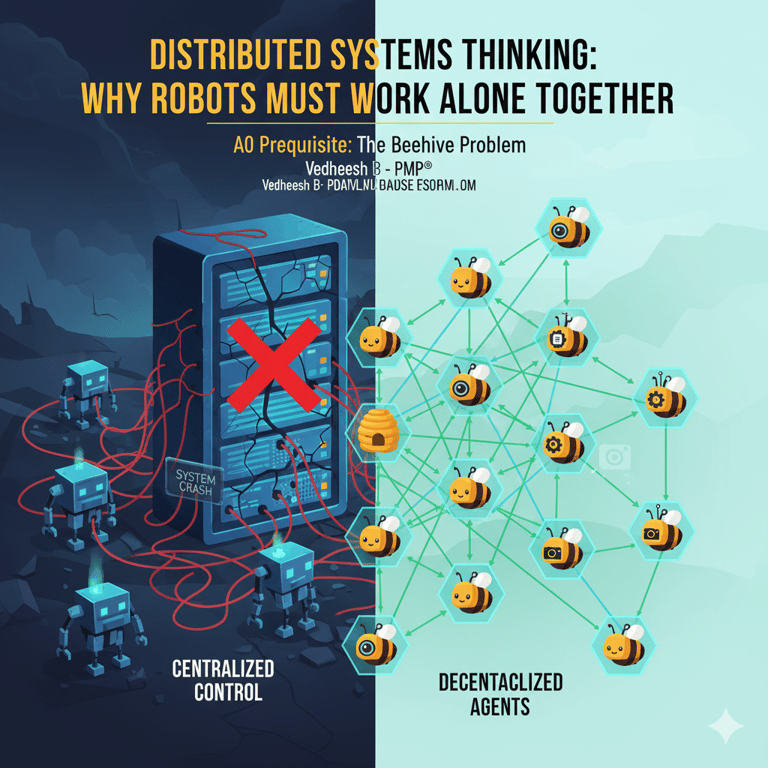

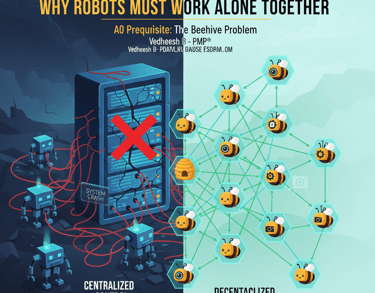

The Beehive Problem: First Mental Model

Imagine a beehive. Forty thousand bees. No CEO. No cloud server. No central database tracking every bee's location and task. Yet the hive thrives; foraging, defending, reproducing, surviving.

How? Each bee has local sensors (pheromones, vision, touch) and makes independent decisions. Scout bee finds flowers → returns to hive → dances the location → other bees decide if they care. No approval needed. No waiting. No bottleneck.

The collective emerges from local interactions, not global commands.

Now ask yourself: Why would we design a robot any other way?

A robot in a real environment faces the same problem as a bee. It operates in a world where:

Networks fail. WiFi drops. Packets get lost. Latency spikes. Communication is unreliable, not guaranteed.

Central servers die. If your robot relies on a master controller and that controller crashes, your entire robot freezes. Not just slow. Freezes.

Real-time matters. Decisions need to happen now, not after waiting for a response from a central authority.

Environments are dynamic. A robot can't ask permission before reacting to an obstacle. It must act locally, then broadcast what happened.

This is why roboticists don't build robots like traditional software. We build them like beehives: autonomous agents that share state, not slaves waiting for orders.

That's distributed thinking. And it's the foundation of ROS2.

Why Centralized Control Fails: Three Real-World Failure Modes

Let's be concrete. Here are three systems that tried centralization, and here's what broke.

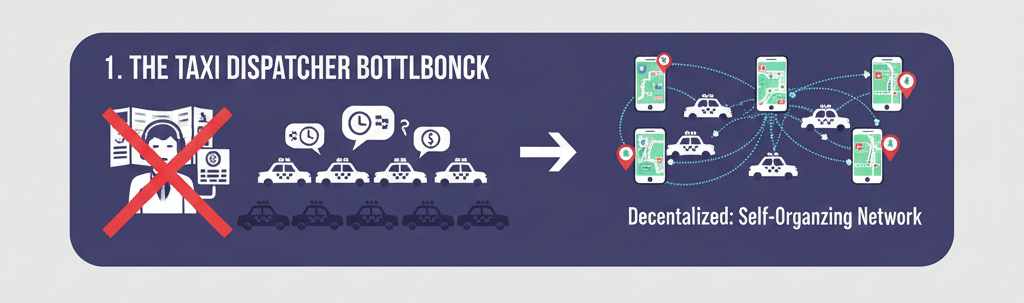

Failure Mode 1: The Taxi Dispatcher Bottleneck

Old taxi system: A dispatcher sits in a central office with a radio. Drivers call in, dispatcher assigns rides, dispatcher handles disputes, dispatcher manages routes.

What happens when a ride goes wrong? Or when demand spikes? Or when the dispatcher gets sick? The system can't adapt faster than one human can handle. Bottleneck = capacity ceiling.

Modern system: Drivers see ride requests on their phones. Each driver decides independently: "This ride makes sense for me." Passengers see multiple drivers. The system self-organizes without any dispatcher.

Better? Yes. Faster, more robust, scales infinitely.

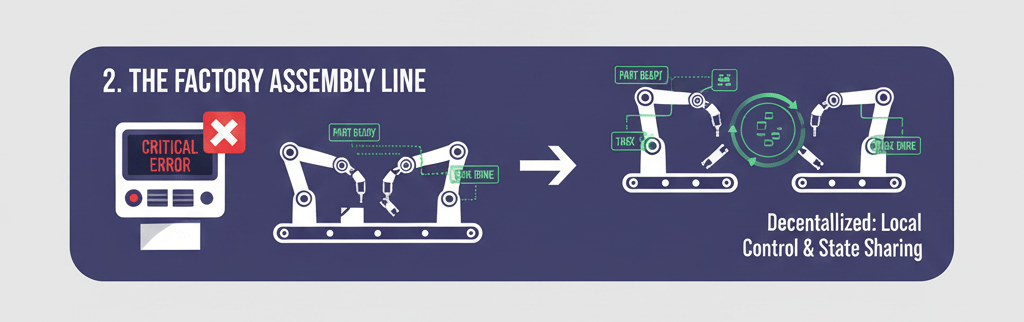

Failure Mode 2: The Factory Assembly Line

Old setup: A central master controller sends commands to 10 robots on an assembly line. "Robot 1, pick part. Robot 2, place part. Robot 3, drill." One master orchestrates everything.

What if the master crashes? All 10 robots freeze mid-task. Safety hazard. Downtime = lost money.

New setup: Each robot has local control. Robot 1 knows "pick a part from conveyor." Robot 2 knows "wait for part from Robot 1, then place it." They don't ask permission. They share state: "part is ready" → "I received it" → "I finished placing it." If Robot 1 fails, Robots 2-10 can still work (just starved for parts).

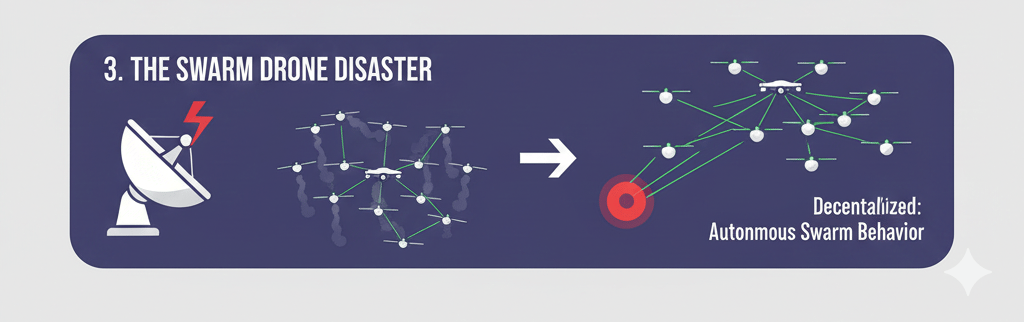

Failure Mode 3: The Swarm Drone Disaster

Old approach: A ground station computes a flight path for 100 drones and broadcasts it to all of them. "Drone 1, go to (10, 20, 50). Drone 2, go to (11, 20, 50)." Etc.

Network fails? All 100 drones fall from the sky.

New approach: Each drone knows its role: "maintain 1 meter distance from neighbors" and "fly toward objective." If the network drops, they still fly safely because they're not waiting for a command. They adapt based on what their neighbors are doing.

The Pattern: Decentralized systems are not fancy. They're resilient. Real robots need them.

What "Distributed" Actually Means: Four Properties

When engineers say a system is "distributed," they mean four things. Understand these, and you understand why ROS2 is structured the way it is.

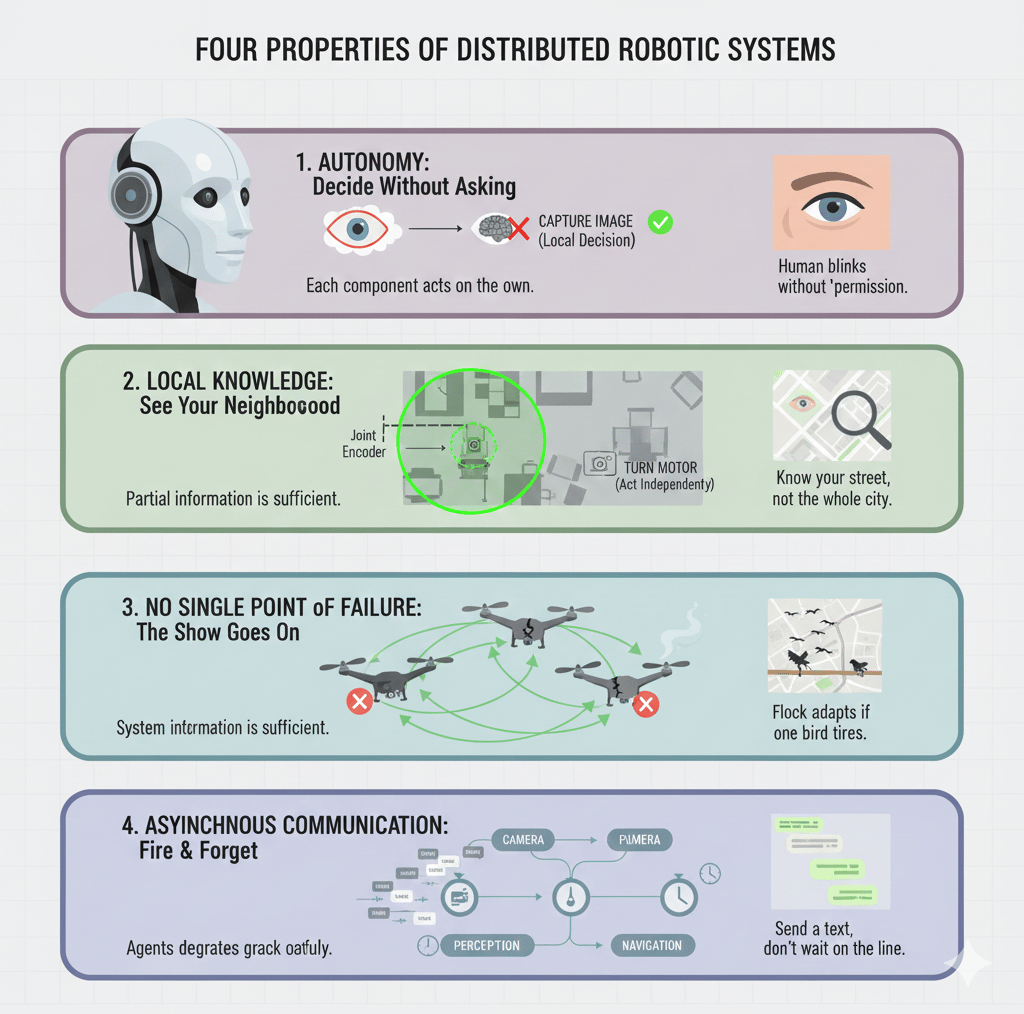

Property 1: Autonomy

Each agent makes decisions without asking permission.

You don't ask your brain for permission to blink. Your eyes just do it. Your nervous system has trillions of cells all making local decisions.

In a robot: A camera doesn't wait for central approval to capture an image. It just does. A motor controller doesn't ask "may I turn?" It reads its command and acts.

Why? Because asking permission creates latency. And latency kills responsiveness in dynamic environments.

Property 2: Local Knowledge

Each agent only knows about its immediate surroundings, not the whole truth.

You don't know what's in every store on your street. You know your neighborhood. You see what's in front of you. You act on that local knowledge.

In a robot: A camera only sees its field of view. A lidar only sees within its range. A joint encoder only knows its own angle. No sensor sees "the whole robot" at once. Each sensor is a local agent with partial information.

Why? Because global knowledge requires communication. And communication is expensive in robots (bandwidth, latency, power).

Property 3: No Single Point of Failure

If one agent dies, the system continues working.

A flock of birds doesn't stop flying if one bird gets tired. The flock adapts, self-organizes.

In a robot: If one sensor fails, the others keep working. If one motor dies, other motors can compensate (or keep running). If one communication link breaks, other links still work.

Why? Because real systems break. Real robots get damaged. Distributed systems degrade gracefully instead of catastrophically.

Property 4: Asynchronous Communication

Agents don't wait for each other to respond.

You send a text. You don't hold the phone and wait on the line for a reply. You go about your business. The reply arrives when it arrives.

In a robot: One node publishes a sensor reading. It doesn't wait for other nodes to process it. It just sends it out. Other nodes read it when they're ready.

Why? Because waiting = blocking. And blocking = slow, brittle systems. Asynchronous = fast, resilient.

Three Ways Independent Agents Coordinate (Without a Boss)

Here's the insight that explains ROS2's entire architecture: there are only three patterns for agents to coordinate without a central authority.

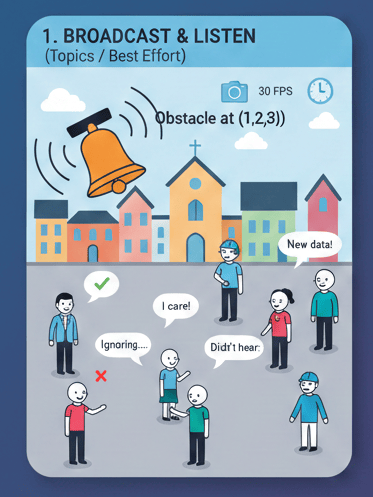

Pattern 1: Broadcast & Listen (Best Effort)

Agent A says something out loud: "I see an obstacle at position (1, 2, 3)!"

Agents B, C, D can listen (or ignore). No handshake. No acknowledgment needed. Fire and forget.

Real-world analogy: A town alarm bell rings. People who care respond. People who don't hear it or don't care just keep going. The alarm bell doesn't wait for everyone to acknowledge.

Use case: Continuous data where

freshness matters more than guarantee.

Camera publishing images

(30 FPS — old frames are disposable)Sensor publishing readings

(once per second)Status broadcasts

("I'm healthy", "I'm moving")

Problem with this pattern:

What if the network is slow? The receiver gets stale data. What if the network drops a message? The receiver misses it. This is acceptable for continuous streams (the next image is coming in 33 milliseconds anyway). Unacceptable for critical queries.

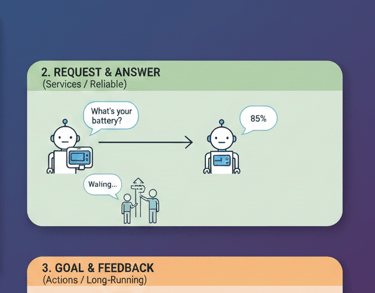

Pattern 2: Request & Answer (Reliable)

Agent A asks Agent B a specific question: "What's your current battery level?"

Agent A waits for an answer. Agent B must respond. If B doesn't respond in time, something's wrong.

Real-world analogy: You ask a stranger for directions. You wait for an answer. If they don't answer, you ask someone else or keep looking.

Use case: Occasional queries where correctness matters.

"What's your battery?" (check once per minute)

"Are you ready?" (synchronization point)

"What's the current pose?" (planning query)

Problem with this pattern: It's synchronous. Agent A blocks waiting for B. If B is slow or dead, A is frozen. This is fine for occasional queries (happens rarely). Bad as default (would create deadlocks).

Pattern 3: Goal & Feedback (Long-Running)

Agent A asks Agent B to do a long task: "Move to room 5."

Agent B accepts the goal, starts working, sends progress updates: "20% done... 40% done... 80% done."

Agent A can change the goal mid-way: "Actually, go to room 3 instead." Or cancel: "Never mind, stop."

Real-world analogy: You hire a contractor. You agree on the job. They work on it. They send you weekly progress photos. If the scope changes, you renegotiate. You can cancel if needed.

Use case: Long-running tasks with feedback.

"Navigate to this waypoint" (takes 5 seconds)

"Pick and place this object" (takes 2 seconds)

"Charge your battery" (takes 30 minutes)

Problem with this pattern: It's complex. You need goal acceptance, feedback streams, cancellation logic. Only use when you actually need these features.

These Three Patterns Cover 90% of Robot Problems

That's it. Broadcast for streams. Request-response for queries. Goal-feedback for tasks.

Most roboticists spend years working with robots and never need anything else.

Now here's the key question: Why not just use REST APIs? Or function calls? Or shared memory?

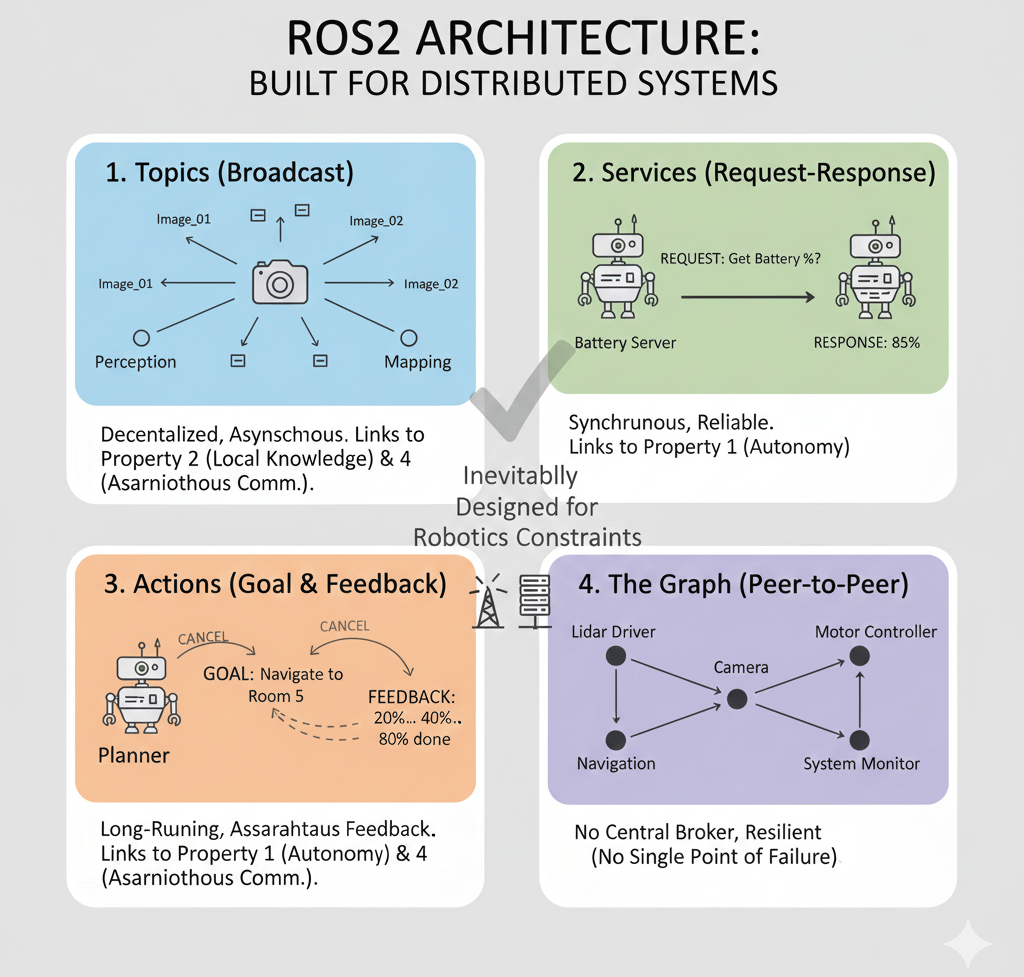

The Four Properties Make Everything Clear

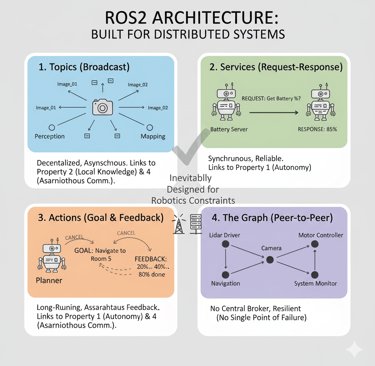

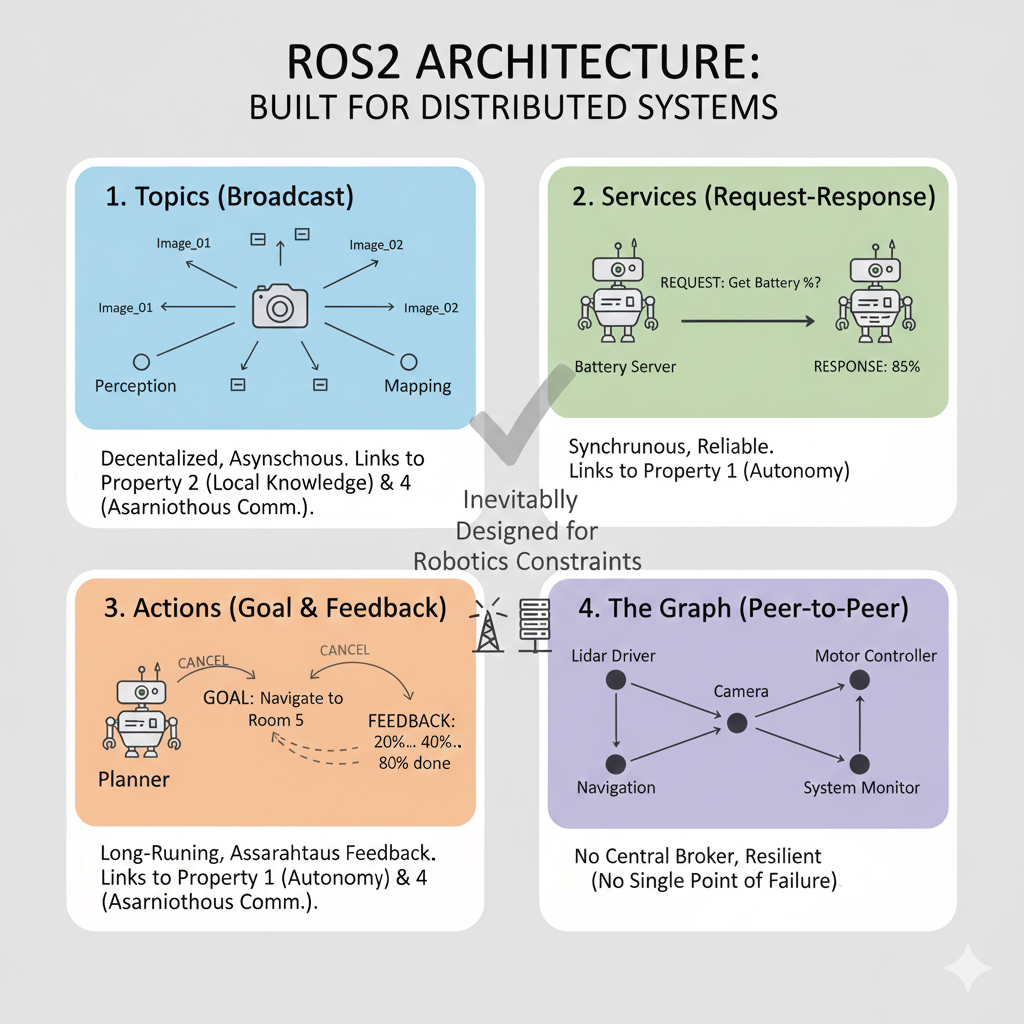

Now you understand why ROS2 has:

- Topics (decentralized, asynchronous broadcast) → Property 2 & 4

- Services (synchronous request-response) → Property 1 (autonomous requests)

- Actions (long-running with feedback) → Property 1 & 4 (autonomous tasks with async updates)

- The Graph (peer-to-peer network) → Property 3 (no central broker)

These aren't arbitrary design choices. They're the inevitable consequence of building systems where autonomous agents operate in unreliable environments with local knowledge.

Why REST APIs (and Most Software Patterns) Fail for Robots

You might think: "Can't we just use HTTP for everything? It's the internet standard."

Here's why that fails in robotics:

REST Assumes Reliability

HTTP assumes: You send a request → you wait → you get a response (or a timeout). The assumption is that something will come back.

Robots don't have this luxury. A WiFi network drops. A USB cable disconnects. A cellular link gets interrupted. The network is a best-effort service, not a guarantee.

If you build on REST and the network stutters, your client times out. Your robot freezes. Unacceptable.

REST Is Synchronous by Default

HTTP is request-response, which means blocking. You wait for the response.

In robotics, blocking is dangerous. Your motor controller shouldn't wait for the main computer to respond before acting. Your sensor shouldn't freeze while waiting for processing confirmation.

ROS2 is asynchronous by default. You publish and move on. If someone cares, they listen. If not, you don't care.

REST Assumes Continuous Connectivity

Software APIs assume you're connected to the network. Always. Reliably.

Robots operate in environments where connectivity is intermittent. You're on WiFi, then you roll into a dead zone. You're on Bluetooth, then it drops. A distributed system should work even when partially disconnected. ROS2 does. REST doesn't.

Example: Battery Query in HTTP vs. ROS2

HTTP approach:

``` Client: GET /api/battery Waits... Network is slow... Waits... Timeout. Client crashes. Or retries. Mess. ```

ROS2 approach:

``` Battery node publishes: battery_level = 85% Anyone who cares reads it. Network is slow? Subscriber reads stale data (last update). Network drops? Subscriber keeps running on last known value. Network recovers? Subscriber gets next update. Continues seamlessly. ```

ROS2 isn't a fancy framework. It's an optimized communication system for robotics constraints.

Common Misconceptions: Addressed Now, Not Later

Misconception 1: "Distributed = More Complex"

False. Distributed is simpler when you understand it. Centralization is complex because you're fighting the nature of the problem. You're trying to squeeze every decision through a bottleneck.

Distributed: Each agent does one thing well. Simple. Scalable. Robust.

Centralized: The master must know everything, decide everything, handle failures. Complex.

Misconception 2: "DDS is Something I Need to Learn First"

False. DDS is the middleware layer that ROS2 uses under the hood. It's an implementation detail. You don't need to understand it yet (maybe ever). ROS2 abstracts it away entirely.

Learning ROS2 without understanding DDS is like driving a car without understanding internal combustion. Perfectly fine.

Misconception 3: "Nodes Talk Through a Central Server"

False. That was ROS1, and it was a weakness. ROS2 has no central master server. Nodes are peers. Graph discovery is automatic and decentralized.

If the "master" dies in ROS2... there is no master. Everything keeps working.

Misconception 4: "I Need to Understand Real-Time Constraints to Start"

False. Distributed systems thinking comes first. Real-time optimization is a later specialization.

Learn to think in decentralized systems. Then optimize. Not the other way around.

Anti-Patterns: What NOT to Build

If you're tempted to do any of these, stop. Your robot will fail.

Anti-Pattern 1: "Make One Node the Brain"

The idea: One "main controller" node decides everything for the robot.

Why it fails: If the main controller crashes, the robot dies. Single point of failure. Also, the main controller becomes a bottleneck—it can't scale.

Better: Each subsystem has its own control logic. Sensor nodes process data locally. Motor nodes execute locally. The "main" node coordinates, not controls.

Anti-Pattern 2: "Use Shared Memory for Everything"

The idea: Store everything in shared memory that all processes can read/write.

Why it fails: Shared memory only works on one machine. Breaks as soon as you add a second robot or a remote computer. Also race conditions (data corruption).

Better: Use ROS2's communication (topics, services, actions). Works on one machine or 100 machines. Automatically handles synchronization.

Anti-Pattern 3: "Wait for Everything to Sync"

The idea: Before doing anything, wait for all subsystems to report "ready."

Why it fails: Synchronization is expensive. Also brittle—if one subsystem is slow, the whole system waits.

Better: Systems should start up asynchronously. A sensor publishes data as soon as it's ready. Other nodes consume it when ready. No waiting.

Real-World Examples: Robotics in the Wild

Example 1: A Mobile Robot with Multiple Sensors

The robot has a camera, a lidar, an IMU, and encoders. Old approach: everything reports to a central "fusion" node.

Problem: The fusion node becomes the bottleneck. Also, if fusion crashes, navigation stops.

Distributed approach: Each sensor publishes its data independently (camera publishes images, lidar publishes clouds, IMU publishes angles). Navigation subscribes to what it needs. If the camera dies, lidar and encoders still work. If navigation temporarily crashes, sensors keep publishing.

Example 2: A Multi-Robot Swarm

You have 5 robots doing collaborative mapping. Old approach: all robots send sensor data to a central server for processing.

Problem: All 5 robots are bottlenecked by the server. Network bandwidth is wasted sending redundant data. If the server is in a distant data center, latency is high.

Distributed approach: Each robot processes its own data locally. Robots share key information (completed maps, obstacles). Each robot acts on its local knowledge and shared state.

Example 3: A Manipulator with Joint Controllers

A robotic arm has 7 joints. Old approach: all joints take commands from a central motion planner.

Problem: The planner must update every joint in sync. If one joint is slow to respond, all others wait. Brittle.

Distributed approach: Each joint has a local controller. The planner publishes target trajectories. Each joint asynchronously follows its trajectory. If one joint is delayed, the arm keeps moving (just asymmetric).

New Mental Model

Stop thinking of robots as "central computers with peripherals."

Start thinking of robots as "distributed teams of autonomous agents that share state."

A sensor is an agent (publishes what it sees)

A motor is an agent (publishes what it's doing)

A planner is an agent (publishes decisions)

They don't control each other. They inform each other.

This mental shift is why you need A0 before A1. Without it, ROS2 feels arbitrary. With it, ROS2 feels inevitable.

🚀 TL;DR

Robots operate in messy, decentralized realities: each has only local sensors, unreliable communication, and partial information, so a single central “brain” is fragile and slow.

Distributed thinking means designing many small, independent nodes that cooperate via well‑defined messages instead of one big process that “knows everything.”

The article contrasts centralized patterns (single dispatcher, single master) with distributed ones (local controllers, peer‑to‑peer coordination), showing how central systems break under latency, failure, or scale while distributed ones degrade gracefully.

It motivates ROS2 as infrastructure built specifically for such distributed robotics: nodes, topics, services, actions, and middleware (DDS) exist to support this style of design rather than as arbitrary complexity.

Core mindset shift: stop thinking “one program that controls a robot”; start thinking “a system of communicating agents that together are the robot.”

How This Connects Forward

Next: In Article A1 ("What ROS2 Really Is"), you'll learn that ROS2 is the tool built specifically for this distributed thinking. You'll see that everything in ROS2—the graph, the nodes, the topics, the services—is a direct consequence of the principles you just learned.

Learning Outcome Test

After reading this article, you should be able to:

1. Explain to a non-roboticist why a robot can't rely on central control (even though it seems simpler)

2. Describe the three ways agents coordinate (broadcast, request-response, goal-feedback) without using the words "topic," "service," or "action"

3. Predict which communication pattern would fail in an unreliable network and why

4. Defend the statement: "ROS2's design is optimized for robotics, not arbitrary" by referencing the constraints robots face

5. Catch yourself thinking "why doesn't ROS2 just use REST?" and immediately answer your own question

If you can do these five things, you've internalized distributed thinking. Everything that follows will make sense.